- Home

- Neville Peat

High Country Lark Page 3

High Country Lark Read online

Page 3

Novelist Isabel Maud Peacocke, in The House at Journey’s End, relates a love story about an Auckland woman, jilted in love, who travels to Paradise for a winter adventure and finds love again. ‘… a paradise it is to those who like scenery and plenty of it, snow-covered peaks, frost-bitten lakes, ice, rivers, beech forests, mist and rain and snow, icicles on the bushes …’ What would Fenn have made of it? He rarely left Arcadia and died the year before the book was published, 1925.

Being so far west, Paradise has daylight till well after 10 p.m. at the summer solstice. Usually I’d take advantage of it — especially as Geoff Ockwell knows enough about Paradise and the Head of the Lake to fill a book — but I need to get an early night. Anyway, he has a guiding assignment the next day for some visitors staying at the Blanket Bay Lodge near Glenorchy. Before heading for my hut, I wander around to the front door of the fabled Paradise House. Its frontage has seen better days, for sure. But the old horse chestnut tree is still there. Geoff tells me there are masses of polyanthus, in colourful, sweet profusion, under the tree in spring, and dainty white-tailed deer munch on the fallen chestnuts in autumn. These deer, introduced to the area in 1905 from New Hampshire, USA, live within about a twenty kilometre radius of Paradise. Leaping fences, they may leave their usual haunts in the beech forest to graze Arcadia’s paddocks with the sheep and Simmental cattle during the day. Here the deer are protected.

My overnight accommodation is set back into the forest about 150 metres from Paradise House. It is a red-brown weatherboard unit in a clearing called ‘Bushvedlt’, a South African term a long way from home. The hut’s commodious main room is equipped with a coal range, kitchen area, and two single beds, and there is a shower and porch off it. On the West Coast, you might hear such a dwelling described as a ‘hut-house’. I whip up a quick brew on my gas cooker under candlelight, for the beech forest has wrapped the little clearing in a premature dusk, and retire to my sleeping bag.

Paradise, I soon discover, has things that move in the night. A tiny nip on my ear suggests an insect; scuffling noises suggest something larger. Mice! When the beech trees seed, as they have done this year, mice in plague numbers are usually the result. Now they are clattering about the hut, and I catch some of them in the beam of my torch. Perhaps driven by the hunger created by overpopulation, they are not the least bit scared of a visitor rustling in a sleeping bag. One or two scamper over the bottom of the bag.

I recall reading about a plague of rats encountered by the very first Europeans to reside and work at the Head of the Lake. Alfred Duncan, a Scottish shepherd assigned to look after the stock on the first sheep run, in the Rees Valley in 1861, told of rats eating their ropes, tobacco and practically anything not made of metal. ‘They swarmed over us at night … we several times were aroused by their pulling at our hair.’

The rodent ruckus in Bushveldt eventually gets to me. I retreat to my Mazda wagon parked nearby, lowering the backseats so I can stretch out. It is worth the move just to experience the high-country starlight. Orion is angling its famous belt of stars towards a ragged skyline. Stars and silence, blessed relief. Then I hear mice again. Busy as ever, they are scrambling up the tyres and, by the sound of it, rummaging around under the bonnet. I will see in the morning whether they have disabled my transport by gnawing through electric wires. I’d like to be away early for Sugarloaf Pass.

Film-maker’s darling

Paradise has been the darling of various film-makers in recent decades. In The Lord of the Rings films, the mossy forest of Lothlórien, filled with dappled light, was up the farm road from Paradise, at Dan’s Paddock, and Boromir died in an area of forest close to Paradise House, called Amon Hen (pictured below). Narnia’s Prince Caspian and a drama, Vertical Limit, also made use of the mountains and the forest, as did a fantasy movie called Wolverine, part of the X-Men series. But Paradise has had some of its charm knocked off during the making of these films, with a mess made in some of the moss gardens, and helicopter noise a nuisance to residents.

CHAPTER 2

Sugarloaf Pass

‘A very curious circumstance’

Mr Buchanan, of the Geological Survey, has mentioned to me a very curious circumstance frequently observed by himself at Otago: he has seen these birds travelling through the bush on foot, Indian fashion, sometimes as many as twenty of them in single file, passing rapidly over the ground by a succession of hops, and following their leader like a flock of sheep; for, if the first bird should have occasion to leap over a stone or fallen tree in the line of march, every bird in the procession follows suit accordingly!

From Sir Walter Buller’s notes on South Island kōkako,

A History of the Birds of New Zealand, 1888

Around seven o’clock in the evening, two days after the 1995 summer solstice, a graduate student from Harvard University, Cagan Sekercioglu, who is of Turkish descent, crossed the swing-bridge at the start of the Routeburn Track from the Glenorchy end, and set off at a brisk pace for the camping spot at Routeburn Flats. He was alone. The weather was clear, the light good.

He had hiked about a quarter of an hour and was close to the second swing-bridge, which crosses Sugarloaf Stream, when he saw a bird close to the track, low down. It was about twenty metres away. A bird biologist and wildlife photographer, Cagan knew he was looking at something different to what the guidebooks told him to expect in these southern forests. The bird, a dark-grey shape in the twilight, made no sound, and the forest itself was quiet. As he reached for his binoculars, the bird moved farther away from the track. But it stayed within his line of sight and he got a clear view of it for a few moments before it was gone.

‘When I first saw it,’ Cagan wrote in an ‘incident report’ for the Department of Conservation a few days later, ‘I thought it was a huia.’ But then he remembered huia were extinct, and anyway, they were North Island birds. The reason he thought of huia first was because of the ‘prominent orange wattles’ on the bird (huia had orange wattles, as do South Island kōkako). He’d already seen saddlebacks, a related wattle bird, on his travels in New Zealand and knew he wasn’t looking at a saddleback. It had to be a South Island kōkako, the only other possibility among the ancient family of New Zealand wattle birds. He knew it was rare if not extinct. It was, he wrote, using the scientific name for the family, ‘definitely a callaeid’.

Cagan continued on to the Routeburn Flats, pitched his tent there and wondered what to do about what he’d just seen. When I contacted him several years later, by which time he had a Ph.D. from Stanford University in the causes and consequences of bird extinctions in tropical countries, and was working as a bird conservation specialist with a long list of projects to his name, he recalled having doubts about whether he should report the Sugarloaf Stream sighting. He was worried he might be regarded as an attention-seeking ‘stringer’ — a foreigner to boot. ‘Stringer’ is an American term for a birdwatcher who fakes sightings of rare birds.

In the end, his conscience was tweaked. He decided that he couldn’t ignore the conservation implications of not reporting a kōkako in the Routeburn area. Moreover, he would have felt, as he put it, ‘very guilty not mentioning it’. After completing the Routeburn tramp he contacted the Department of Conservation office in Dunedin, the government agency responsible for protecting endangered species, and wrote out the incident report. Cagan had come to New Zealand at the end of a three-month project in the World Heritage rainforest of the Atherton Tablelands, Northern Queensland, and returned to the United States to continue his studies and an international career in bird conservation.

The 1995 Sugarloaf Stream sighting is significant. For a start, it is relatively recent in the sketchy history of the species, reports of which pepper the records of rare-bird sightings through the last half of the twentieth century. The Department of Conservation (DOC) believes the South Island kōkako is gone for good. In January 2007, a DOC report stated there had been ‘no confirmed sightings for forty-five years’.

That statement is questionable. The pivotal word is ‘confirmed’. There have been numerous ‘sightings’ (but no photographs of sufficient clarity) and reports of distinctive calls in recent decades. Although there hasn’t been enough evidence to convince the classifiers of threatened species at the Department, applying the designation ‘Extinct’ is a big call.

Of several reliable sightings in the twentieth century, a stand-out is the report by a deerstalker, K. McBride, of two sightings in successive years, 1966–67, in the same area of the little-visited Tiel Valley near Makarora, north of Lake Wanaka. In May 1966, the hunter saw a kōkako on a branch at the edge of beech forest. He reported ‘putty coloured’ wattles and a black face. ‘One could imagine it wearing a mask,’ he said. The second sighting, in April 1967, was of a kōkako walking along a sloping log: ‘… it climbed the trunk in a most peculiar way. With each rather ungainly step upwards, it appeared to hold on to the bark with its beak, take a look at me, take another step … till it reached branches, when it hopped rapidly out of sight.’ Several years later, an expedition that included officers from the Wildlife Service and the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) Ecology Division failed to locate any birds.

More recently, through the 1980s and 1990s, sporadic sightings or calls indicative of kōkako have been reported from the Wakatipu region — from the valleys bounding the Head of the Lake, the Greenstone, Caples, Routeburn, Earnslaw Burn and Rees. A scatter of reports — sightings, calls and kōkako-like moss grubbings, first noticed in the Tiel Valley incidents — emanated from expeditions made into the Upper Caples in 1983–84 by a group of dedicated ornithologists, including Peter Child and Rhys Buckingham. They knew what to listen and look out for. Other reports were from people without an educated eye or ear for kōkako but who clearly heard, and sometimes saw, something unusual. Cagan Sekercioglu’s sighting near Sugarloaf Stream falls somewhere between ‘expert’ and ‘non-expert’. Although he was a student at the time, his experience and academic achievements have since multiplied, and no one would deny his credibility now.

In all, the evidence points to the real possibility that kōkako, in very small numbers and widely distributed, were surviving in forests at the Head of the Lake towards the turn of the century. With all this in mind, and a trip to Sugarloaf Pass in prospect, I thought I had better familiarise myself with kōkako calls.

The ‘go to’ man on South Island kōkako vocalisations is John Kendrick, now living at Waipu, just south of Whangarei. I have met Johnny a number of times. A sound recordist with the New Zealand Wildlife Service for twenty years, and the originator of the bird calls you hear on the hour during Radio New Zealand National’s Morning Report, he is one of nature’s most ardent enthusiasts. An animated fellow, now well into his eighties, Johnny shows little sign of slowing down. He talks as if his mind is whirring like a tūī’s wingbeat. Recent excursions are his favourite topic. When I phone to ask if he could send me any recordings of South Island kōkako calls, he tells me excitedly about his recent ascent (his third in a year, with botanists) of a 400-metre hill overlooking Whangarei Harbour. Certainly Johnny has done the hard yards in the wilds of New Zealand, lugging heavy sound-recording equipment into some pretty remote places.

And it’s not easy keeping up with impassioned bird researchers on the trail of the obscure. Rhys Buckingham is among them — my choice for an ‘iron man of ornithology’ award if ever such a thing is created. Based at Mapua in the Nelson region, Rhys has made the rediscovery of South Island kōkako his mission in life. His first glimpse of a South Island kōkako was on Stewart Island in 1977 in a tributary of the Freshwater River below Mount Anglem. He saw the bird — a ‘large, longish-tailed grey bird’ — after hearing a penetrating and melodic call during steady rain, when most birds go silent. The kōkako sang from high up in the canopy of mature rimu trees. Before he confirmed the call as coming from a kōkako he thought it sounded like a mixture of tūī and bellbird notes. In the 1980s he and Johnny Kendrick journeyed into the Upper Caples, Stewart Island and Northwest Nelson in search of kōkako.

The kōkako calls on Morning Report are of the North Island kōkako, which survives in viable numbers with the assistance of a recovery programme. Rarely have the calls of the South Island bird been recorded. I’m told the calls of the two birds differ. I expect Johnny’s collection of the southern bird’s calls to include some of the more bizarre sounds. On the phone, he apologises to me in advance for the tape’s background noise and lack of clarity.

‘Quality’s not the best,’ he says. ‘The recording equipment wasn’t as good as you get these days. That, and the calls were sometimes coming from a fair way off. I’ll send you a tape tomorrow.’ Not one to mess about, is Johnny.

Classical peaks

Names from Greek and Roman mythology proliferate in the Humboldt Mountains and along the Main Divide in this area, among them Cosmos, Somnus, Minos, Mercury, Apollo, Nox, Nereus, Poseidon, Amphion, Niobe, Erebus, Chaos and Pluto.

These are the mountains of the gods, the mountains of myth.

Some of them — Cosmos and Somnus, for example — were named by James McKerrow, who led reconnaissance surveys through the region in 1862–63. A Scotsman, McKerrow was assigned by his boss, the Chief Surveyor of Otago, John Turnbull Thomson, to go and fill ‘the blank on the map’ known as the southern lakes district.

Over time, more names of Greek and Roman gods and mythological figures were attached to these mountains. Arcadia Station founder Joseph Fenn produced a few of these names. Some have been officially gazetted after deliberation by the New Zealand Geographic Board, others have the status of ‘recorded names’ — that is, they appear on maps and have become accepted by general usage but have yet to be gazetted, and the proposers of these names, settlers and mountaineers perhaps, are not easily identified.

Given his brief to fill a ‘blank’, McKerrow may not have known that Māori overlanders had their own names for the peaks, some of them representing spiritual beings. The highest peaks between the Dart Valley and the Beans Burn he named Cosmos, from a Greek word meaning an ordered whole or system and a synonym today for the universe. Pre-European Māori knew the same mountains as Koroka. From a certain place on the Dart River, the skyline of Koroka took the shape of a giant’s face lying down — a landmark of immense significance to these early people. It guided them to the source of their most precious stone, pounamu/greenstone.

Mountain ranges such as Humboldt and Forbes were named by James McKerrow after distinguished men of science. Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) was a Prussian naturalist and explorer who travelled in Latin America and inspired the discipline of biogeography. His crowning literary work was called Cosmos. James David Forbes was a professor of natural philosophy at Edinburgh University from 1833 to 1860.

The cassette tape arrives in the post. The calls run for about ten minutes. Johnny’s voice announces the collection as ‘Calls of presumed South Island kōkako’. Applying scientific caution, he puts an emphasis on the word, ‘presumed’. He has never seen and heard a South Island kōkako at the same time. He saw the ‘tail end’ (feathers fanned) of a bird in flight, presumed to be a kōkako, in Stewart Island’s Freshwater River catchment in the 1980s. But he has heard some amazing things, and the cassette tape he has sent me contains them, each sequence preceded by an announcement of the place and month of the recording. They are all from the 1980s — from the Caples Valley, Stewart Island and Rocky River, which is in Kahurangi National Park, northwest Nelson.

The ‘bong’ call is up first, from the Caples Valley in December 1983. It is among the first calls ever recorded of South Island kōkako, certainly the first that Johnny ever heard. Rhys Buckingham was with him that day, and saw how the call immediately ‘transformed’ Johnny. Listening to the resonance of the taped single note over and above a background hiss and the calls of other birds, I find it remarkable. It is the call with the most ‘carry’ of any forest bird. Rhys reported such calls as carrying more

than a kilometre in the right acoustic conditions. Kōkako surveys in the Caples around this time identify features such as the ‘Kōkako Tree’, where birds were seen, and calls were recorded by Johnny, and Callaeas Flat, named by Peter Child after the kōkako family name and a bunch of sightings there. One such sighting was by Peter himself: in which he described a bird running ‘in giant strides’ up the leaning trunk of a mountain beech tree — clearly not a blackbird and too long-legged to be kākā. On elegant legs, kōkako run, bound and hop — the ‘squirrels’ of the New Zealand forest.

The next calls on John Kendrick’s tape, recorded on Stewart Island, are rather more difficult to describe. For one of these calls, delivered as a couplet, imagine two solid sticks being knocked together and lay that sound over the top of the short, sharp screech of a pūkeko. Then there is a sound somewhere between a staccato bark and a cough or grunt: a series of half a dozen short, deeply delivered ‘huh, huh’ sounds that rise and fade away. To make sure Johnny has not mixed up bird calls with the noises made by an animal — what I have in mind are exotic animals from, say, the South American jungles! — I phone him.

‘Yes, sticks banged together — that’s pretty close to it,’ he says.

‘And the barking?’

‘Maybe.’

‘Johnny, could Stewart Island’s white-tailed deer be making these sounds?’ I am flailing around for an animal to blame.

‘Perhaps it could. But show me a deer that can get thirty feet up a rimu tree. That’s where the sound was coming from. Couldn’t see the bird.’

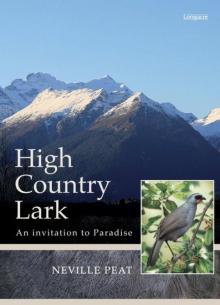

High Country Lark

High Country Lark