- Home

- Neville Peat

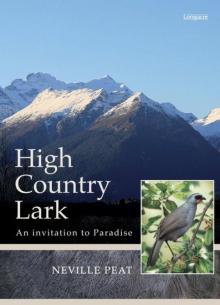

High Country Lark

High Country Lark Read online

An unusual summons from an old, itinerant acquaintance — known as the Lark — piques author Neville Peat’s curiosity. The invitation to meet in the mountains around Glenorchy is timely: he’s keen to head into the high country to investigate recent reports of sightings of the near-extinct kōkako.

The South Island high country has an allure all its own. New Zealand’s equivalent of the Wild West, it’s a rustic, spectacularly beautiful frontier, combining wild alpine beauty, beech forest and mirror-still lakes. The Head of Lake Wakatipu has attracted Māori for the dazzling local pounamu; its sublime beauty has seduced European tourists, artists, writers and farm-holders since the nineteenth century.

Peat sets off on a fascinating trail that takes him deep into the hills to explore local history, legend and land politics. He skilfully blends the characters and stories of the past — those of Arawata Bill and Joseph Fenn among them — with a powerful sense of place and concerns for the future.

In prose as fine as snow-caps reflected in lake water, Peat brings us an extraordinary region: from the laconic humour of the locals, to the last chance we might have to halt the demise of several threatened native species.

High-Country Lark is the third in Peat’s acclaimed Lark series: the first two of which are The Falcon and the Lark and Coasting: The Sea Lion and the Lark.

High Country Lark

An invitation to Paradise

NEVILLE PEAT

Contents

Title Page

An Invitation

1 — Accessing Paradise

2 — Sugarloaf Pass

3 — Character town

4 — Starlight Hotel

5 — Going West

6 — Blades and Traps

7 — The Far Side

8 — The Races

Appendices

References

Index of names

Acknowledgements

Copyright

The Scene

Mountains nuzzle mountains

White-bearded rock-fronted

In perpetual drizzle.

Rivers swell and twist

Like a torturer’s fist

Where the maidenhair

Falls of the waterfall

Sail through the air.

The mountains send below

Their cold tribute of snow

And the birch makes brown

The rivulets running down.

Rock, air and water meet

Where crags debate

The dividing cloud.

In the dominion of the thorn

The delicate cloud is born,

And golden nuggets bloom

In the womb of the storm.

Denis Glover, from

Arawata Bill: A Sequence of Poems, 1953

An Invitation

The invitation arrived in the post on a day somewhere between spring and summer. It was rock-solid. Inside the A5 bubble bag was a flat piece of stone, saucer thin. From the shade of grey, the smoothness of the surfaces and the brittle edges, I guessed it might be schist, the country rock of inland Otago. Scratched on one side, in pencil, were the words:

Sugarloaf Pass.

Solstice 21/12, Noon.

Deo Volente.

Lark

The cryptic message, more like a summons, was from a high-country acquaintance of mine, the Lark. The Glenorchy postmark told me the rendezvous location. Sugarloaf Pass was off the Routeburn Track in the mountains north of Glenorchy. I looked for a return address. There wasn’t one. That didn’t surprise me. I knew the Lark to be a free and independent traveller. He practically coined the term.

I’d last seen him at Taieri Mouth in the late 1990s, when I was looking out for the New Zealand sea lions on the beach there, and he turned up with a white-water kayak in the hope of gambolling in the surf with one of the sea lions. In earlier years I encountered him in the handsomely wide Strath Taieri valley, through which the Taieri River runs. At the time I was researching my ancestral roots there. The Peats farmed the Strath Taieri district from the 1870s, and the Aysons (my mother’s side) arrived in the valley around the turn of the century. The Lark, no relation of mine at all, worked on the district’s sheep farms — an itinerant shepherd and rouseabout. He knew a lot about the nature of the place, its plant and bird life, and especially its falcons. In spare moments — and there were a fair few of those — he would go hang-gliding, with or without his trusty sheepdog, Rocky. In the right place (usually the skyline of Taieri Ridge, above the dun landscape of schist tors and tussock grasses), and at the right time (when thermals allowed a glider to soar), he could be joined in the air by a young falcon he’d rescued as a chick. He had a few yarns in him, the Lark.

Now, seemingly, he had more for me. The invitation to meet him in a wild spot in the high country included the phrase ‘Deo Volente’ (Latin for ‘God willing’). DV, for short. The Lark used to call my ageing Commer camper van Dee Vee after the letters on the number plate, DV4332. He saw in the letters a phrase his father brought home from war service in Italy.

But what was the Lark doing in the mountains and valleys way out west? He had to be well into his sixties by now. I couldn’t imagine his retirement. I reached for an atlas. It placed Sugarloaf Pass at 1,154 metres and accessible from near the start of the Routeburn Track, a popular alpine tramping experience that crossed the Main Divide. The Lark had always been fit. In the Strath Taieri he could spend hours chasing hoggets down from the tops for crutching. He could blade shear sheep all day. Mustering rangeland country on foot, he seemed able to flow up hills — or used to, anyway.

What did I know of the Glenorchy area, the Head of Lake Wakatipu? Battalions of trampers, and I have been among them at times, pass through this landscape every summer. Routeburn. Rees-Dart. Greenstone-Caples. These are celebrated names for any outdoors enthusiast. Most people stick to the tracks. The Lark, I reckon, would want to avoid the beaten ones.

For motorists the Head of the Lake is a cul-de-sac, road’s end. It is also the western limit of farming in Otago. Its steep mountains, tumbling rivers, moss-bedecked beech forest, and snow and ice in high places speak of a mountain fastness and wilderness dramatically arrayed — ‘Middle Earth’. Some scenes in The Lord of the Rings movie series were filmed here. I knew, too, the district had a place called Paradise; a road sign says so. Less obvious are the characters who’ve called the Head of the Lake home over the years, from the refined to the rough-and-ready. Some have become legends. Bill O’Leary for one — Arawata Bill, frontiersman.

The Head of the Lake is still a frontier, the edge of Mount Aspiring National Park. It ought to be a haven for wildlife. For a number of native birds, though, life is a struggle. Mohua (yellowhead), South Island robin, kaka, kea and rock wren inhabit this frontier — but only tenuously. Introduced predators give them a hard time. Then there is the saga of the South Island kōkako, the so-called orange-wattled crow, declared extinct by the Department of Conservation in 2007. There have been unconfirmed sightings, or reports of kōkako-like calls, in valleys bordering the Head of the Lake as recently as the mid-1990s. Elsewhere in the South Island, intermittent reports continue to come in — even as I write this story — from people claiming to have glimpsed or heard kōkako in remote places. I am intrigued. I need to know more. This invitation from the Lark is timely.

CHAPTER 1

Accessing Paradise

Devon cream and sunny lakes

Snowy Peaks and currant cakes

Strawberries and moonlight walks

Home made wine and pleasant talks

Feed on the glories of the Dart

Sandwiches and Rhubarb tart

An entry in the Paradise House Visitors’ Book in the 1890s.

A

t Bennett’s Bluff, 200 metres above Lake Wakatipu and about halfway along the Queenstown-Glenorchy road, you can pull off the road and inspect a map highlighting the landmarks. On a clear afternoon, with the view mesmerising and the sun lowering in front of you, pulling up is advisable. It’s a long way down if you make a mistake trying to take in the views while driving. In the distance is Paradise. You can’t quite see it but you know it is somewhere in the press of snowy mountains beyond the lake and its dark islands. This is the area generally dubbed the Head of the Lake. A tarseal snake coaxes the eye along the foot of the Richardson Mountains. In the foreground is Meiklejohns Bay, which, on a balmy December afternoon, looks like a Club Med setting. Not that you need to see another resort area. Queenstown is quite enough, a town that markets scenery and mainlines adrenalin. Bumper-to-bumper traffic at peak times, clusters of construction cranes and a blur of advertising signs together mark the frantic face and pace of an international tourist destination. You crawl on through, feeling relief as a road sign announces the exit to Glenorchy.

At Bennett’s Bluff, take a break, take your bearings, let the dramatic skyline own your appetite for new horizons. In the late 1870s, the Melbourne-based Austrian artist Eugène von Guérard did just that, though seemingly from a bit farther up the lake and from a lower vantage point. He recorded the scene in an oil painting about the size of a door sideways, titled ‘Lake Wakatipu with Mount Earnslaw, Middle Island, New Zealand’. I saw it when an exhibition celebrating 200 years of New Zealand landscape painting toured the country. It captures the vivid morning light, the haughty twin peaks of Mount Earnslaw/Pikirakatahi and their white pinafore, the Earnslaw glacier; arrowheaded Mt Alfred as a centrepiece; Sugarloaf a foothill out to the left; and seductive valleys everywhere, with the whole peaked panorama reflected on a turquoise lake. Never mind the overly-steepened mountains, an art style of the era, nature here appears all-powerful, even God-ordained. Solitude abounds amid the grandeur. But see what the artist has also caught: a vessel under sail, crossing the lake and somehow finding a breeze. It resembles a Māori waka of ocean-going size — a noble invention, perhaps added for scale.

Von Guérard, who worked out of the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, produced the painting from sketches he made during his New Zealand visit. He would have been in his mid-sixties then. How did he reach his vantage point? By boat, or by walking or riding the rough bridle track from Queenstown? He was ninety years too early to travel by a proper road, and about ten years too early to appreciate guest-house hospitality at Glenorchy.

Except for the sailboat, his expansive view of the Head of the Lake contains no sign of human activity. Twenty years after von Guérard’s tour, in 1898, the Head of the Lake was featured in an issue of postage stamps — recognition of the area’s scenic power and increasing prominence. These stamps were New Zealand’s very first pictorial issue. Curiously, the artist placed a sailboat on the lake, just as von Guérard had done. The picture even replicated von Guérard’s grove of cabbage trees in the foreground. The ‘Mt. Earnslaw’ scene, less panoramic than von Guérard’s, adorned the 2½d stamp. The scene was accurate enough but the spelling of the location as ‘Lake Wakitipu’ did cause a stir. The stamps were swiftly reprinted.

In those days, the lake’s name was likely to be abbreviated to ‘Wakatip’, and you still hear the lake called that. Here’s what the nineteenth-century English novelist, Anthony Trollope, wrote in 1872: ‘I do not know that lake scenery can be finer than that of the upper ten miles of Wakatip.’ The ‘tip’ bit is a contraction of ‘tipua’, the Māori word for something devilish, which hints at a Māori legend involving a giant ogre named Matau, who lived by himself in the hills. The story tells of his kidnapping a beautiful maiden and his subsequent demise at the hands of her rescuer, who set fire to the ogre as he slumbered through a spell of hot north-west föhn winds typical of the area. The fire was so intense it burnt a deep trench in the landscape, which is why the lake is a giant zig-zag, with the northern reach his upper body, the middle reach his thighs with Queenstown at the kneecap, and the southern part his lower legs. His heart survived cremation, though, and still beats at the bottom of the lake, at a prodigious depth, below sea level, causing lake levels to rhythmically rise and fall.

Science explains this phenomenon as a ‘seiche’, from a Swiss term that infers sinking. Apparently Switzerland’s Lake Geneva is similarly affected. Lake Wakatipu’s mini-tides, ranging up to twenty-five centimetres in height and spaced at five to fifty-minute intervals, are caused by variations in atmospheric pressure, winds and water temperatures. They interact in a baffling way. Hydrologists and mathematicians resort to tongue-tying terminology to try to explain it. The lake’s distinctive shape is not easily explained by science, either. A fault line today cuts across the middle of it, about where the backside of the prostrate ogre might have lain. One theory is that the enormous glacier that gouged the bed was simply following drainage channels in terrain much older than the existing mountains.

Enough of the uncertainty. Here are some facts: Lake Wakatipu is New Zealand’s longest lake, at seventy-seven kilometres, and the country’s third largest after Taupo and Te Anau. It first appeared on maps of southern New Zealand in the 1840s (a decade before any Europeans had clapped eyes on the lake, let alone explored its upper reaches) thanks to Māori informants who recounted the oral maps of inland trails.

For Māori travellers of old, the Head of the Lake was a richly rewarding source of a distinctive kind of pounamu or greenstone — and that’s another story. However you view the Head of the Lake today, the reality is inescapable. It’s both an impressive destination and a road-block. The most distant mountains you see from Bennett’s Bluff guard the Main Divide, and there is no way through for an overlander except on foot.

Beyond Bennett’s Bluff, therefore, expect to feel a heightened sense of seclusion. You turned a significant corner a while back that opened up the northern arm of the lake, and now Earnslaw country is drawing you in:

Earnslaw, Eagle’s Hill in the old Scots tongue. You pass a cluster of islands — first, Pig Island/Matau, low-lying and scrubby, then Pigeon Island/Wāwāhi Waka, larger and hillier, where, all too often in the past, visitors’ fires have wiped out tracts of red beech, totara and matai and made life more difficult for the native pigeon, called kūkūpa in the south. These islands, together with tiny Tree Island on the far side of Matau, faced an uncertain future through the ice ages for they lay in the path of the massive Wakatipu Glacier, half a kilometre deep at this point. Its grinding, chiselling power created Pigeon Island’s rounded hillocks.

Farther on, as if to reassure a visitor of connections with the outside world, Glenorchy airfield — small planes only — looms up on the left on a terrace. The town is not in sight yet, but a bronze plaque mounted on a rock commemorates the completion of the tarsealing of the Queenstown-Glenorchy road in 1997. Before then, motoring was a hazardous experience of billowing dust, flying stones and passing bays in places where the road was hair-raisingly narrow.

Coming off the airfield’s terrace you cross the Buckler Burn, deeply entrenched in a narrow, sunless gorge, then the road swings left, straightens up and gently descends along the edge of the Buckler Burn’s shingle fan. Glenorchy is a corner away.

Meanwhile, something is happening to the Humboldt Mountains that form the far side of the lake. Since you passed the islands, this mountain chain has steadily grown in stature in anticipation of its destiny at the Main Divide, meeting point of the east-west watershed. Okay, it’s an illusion but for a few moments the Humboldts do appear to be rising before your eyes, and they are suddenly close and wildly forbidding, forest-clad more than half the way to their ragged crest.

‘Welcome to Glenorchy,’ says a sign at the outskirts of town. ‘Gateway to Paradise.’

There are Pūkeko striding across the streets of Glenorchy, looking like they own the place, when I drive in from the Pacific coast in Christmas week, and there are parakeets sp

rinting across the air space above the village, fearing perhaps an attack by a falcon stooping to conquer. I have heard there are falcons camped in the pine trees on the edge of Glenorchy, and when people come too close to where they’re nesting, they will fly fast and furiously at them. A visitor had a pair of sunglasses perched on her forehead whipped right off her head. How wild is that?

Two teenagers are riding horses on the grass verges in town. There are no formed footpaths here. Come to think of it, there are horses all over the place, grazing paddocks and hot-wired rectangles marked out for subdivision — a scene set to tempt a townie. Glenorchy, population about 200 (300 if you include the outlying runholder families, rural lifestylers and the little settlements of Paradise and Kinloch), is low-profile and laid-back. It is so close to the Head of the Lake that it occupies a river delta at the junction of the lake and feeder rivers. There is the Rees River and a set of lagoons on one side, kept at bay by flood banks, and a smaller mountain torrent, the Buckler Burn, on the other. The town is a flat and spacious grid of streets without street numbers. If you reside here, you are likely to know where most folk live.

And they tend to live in houses painted muted colours: brown, beige, Railways red and various shades of green — colours straight out of a red beech forest. The houses are typically clad in weatherboard timber or corrugated iron, sometimes a combination of the two. Glenorchy is not big on trophy homes — not yet anyway. I’ve noticed subdivision names like Wildburn and Pigeon Place, yet to be fully developed, on a drive around the village. Perhaps the present character is set to change.

There is definitely a new object at the town’s main intersection — new since I was last here — that smacks of big-town status. A roundabout. Queenstown is a parade ground for them. But Glenorchy’s sole roundabout, installed to direct visitors safely towards the Routeburn Track, it seems, is half the diameter and half the height of the Queenstown models. The speed humps on the main street are low-rise, too. They look like flat stones from the local landscape.

High Country Lark

High Country Lark